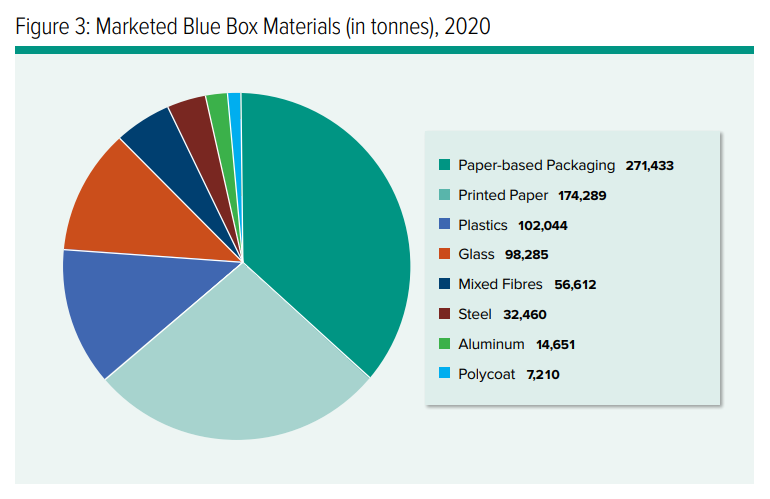

New StatsCan Data Shows Paper Fibres Most Diverted Material

Statistics Canada recently released the results of its Waste Management Survey[1], which includes national waste diversion data for 2023. In this blog, PPEC breaks down the numbers with a focus on paper fibre diversion, discusses the latest plastic figures in the context of recent federal election platforms, and highlights the importance of recycling data. 2023 […]

New StatsCan Data Shows Paper Fibres Most Diverted Material Read More »