This is a story about what’s recyclable, what is sent for recycling, and the fees that stewards of those materials pay into Ontario’s Blue Box system. In what seems like a perversion of the ‘polluter pays’ principle, some of the worst performing materials pay among the lowest fees.

There are two elements to this story. One is that most of the Blue Box materials currently collected in Ontario are recyclable according to Competition Bureau guidelines on environmental labelling and advertising. What that means is that at least 50 per cent of the Ontario population can put them out for recycling.

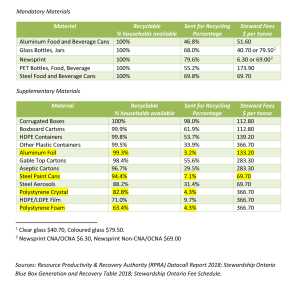

But being ‘recyclable’ (able to be recycled) and being physically sent on for recycling are two quite different things. For example, over 99 per cent of Ontario households in 2018 could place aluminum foil in their Blue Boxes but only three per cent of that foil was sent on for recycling. Similarly, with steel paint cans. Over 94% of households were able to recycle them in the Blue Box but only seven per cent were recycled. And polystyrene foam. Over 60 per cent of Ontario households had access to its recycling but only four per cent was recycled. The largest gaps between being ‘recyclable’ and being sent on for recycling are highlighted in the chart below. Unfortunately, there are opportunities here for greenwashing: standing back and saying that a material is recyclable by households but doing little to increase its recovery.

And the fees that some industry stewards pay into the Blue Box system are not exactly encouraging higher recovery of some of the worst performing materials. Stewards of aluminum foil, for example, with a three per cent recovery rate, only pay $133 a tonne. That’s only $20 more than the stewards of corrugated boxes with a 98 per cent recovery rate! Stewards of steel paint cans, with a recovery rate of only seven per cent, pay even less ($69.70 a tonne). In steel’s case, the stewards of paint cans are riding on the backs of the stewards of steel food and beverage cans, who pay the same amount.

Fees, it seems, need to be more closely targeted at specific materials within a broader group. And part of that targeting is sorting out what a material’s real recycling rate is. What is in the sometimes mixed bales that leave a material recycling facility (MRF) for an end-market, for example, and how much of the different materials in that bale actually end up being recycled?

The current discrepancies between performance and steward fees illustrate the fact that the Ontario Blue Box funding formula gives far more weight to the cost of managing materials in the system than it does to promoting better environmental performance. This is not what former Environment Minister Leona Dombrowsky promised when promoting the new 50 per cent industry-funded Blue Box scheme to a meeting of the Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters way back in 2004: “We plan to send a clear message that in Ontario, good performers are rewarded with incentives while polluters will pay for their actions.”