Green visions, aspirational goals, and political grandstanding are all very well in their place. But at some point, we have to be realistic. The fact of the matter is that the overall waste diversion rate of Ontario’s Blue Box is unlikely to improve much over the next ten years, and the new diversion targets proposed by the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP) will not be achieved.

These are the stark findings of a PPEC-commissioned study by Dan Lantz of Crow’s Nest Environmental. Lantz has more than 30 years’ experience in the waste and recycling industries.

The study examines Blue Box diversion patterns from the current program’s inception in 2003 together with industry reports on the future of given materials and an understanding of the capabilities of the recycling system and end-markets. To establish future generation and recycling rates, all on a per person or per capita basis to account for population growth, the study determines and applies mathematical formulas to predict whether Blue Box materials will meet the ministry’s two new proposed diversion target dates of 2026 and 2030. The answer is no, they won’t.

Blue Box will struggle to make 60%

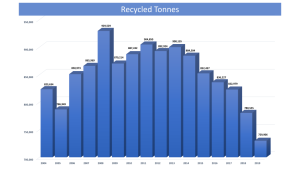

Where are we now? The Blue Box program is currently diverting 57% of the printed paper and packaging that ends up in Ontario homes. Its performance, though, has been steadily declining over the years as lighter and less recycled materials make up a growing portion of the residential waste stream.

The data tell the story. In 2003, the generation of printed paper (mainly newspapers) represented almost half (47%) of the Blue Box materials in Ontario households. By 2019, printed paper’s share of generation had shrunk to 27%. Its share of what was diverted shrank too (from 61% in 2003 down to 30% in 2019).

At the same time, plastic packaging’s share of generation increased from 16% to 25% and its diversion share rose from 5% to 13%. These trends are expected to continue over the next decade and to impact diversion rates accordingly.

And while the ministry has wisely not specified a new overall Blue Box diversion target, its consultation papers make clear it would like to achieve somewhere between 75% and 80% within the next ten years. That’s not going to happen, says Lantz.

“Based on projections out to 2026 and 2030, the ministry’s targets are not realistic under the current program structure.’’ In fact, he says, unless something major changes like the Blue Box giving people more opportunities to recycle (say through an extensive depot network) and the public becomes more engaged and recycles far more than it does at the moment, then the Blue Box will continue to struggle to achieve the existing 60% diversion target into the future. He forecasts just over 58% diversion by 2030.

It’s important to note that the ministry is talking about diversion targets here, not collection targets. It is one thing to measure Blue Box performance by collecting materials at curbside and depots, as British Columbia does. But in Ontario, diversion is measured after the collected material has been processed at a material recycling facility (MRF).

The level of contamination can make a big difference as the higher the contamination the harder it is to achieve better recovery rates. So, BC’s performance (aided by the strategic location of some 250 collection depots) should not be equated with what Ontario is proposing.

Another complication is that the Ontario ministry wants more material diverted from a wider range of sources. This is fine, but broadening how much needs to be diverted (the generation base) automatically reduces the diversion rate as well, because unfortunately not all of that new source material will be diverted.

The only way the diversion rate would improve would be if the new materials achieve diversion rates above the average. Considering that some of the new materials proposed by the ministry for collection (including straws and plastic cutlery which will not be recycled at all because they are too small to be effectively captured and will just end up going to disposal), the diversion rate will not improve above what is projected in the Lantz report.

The province has not offered any estimates of how large this new supply of material will be, making it harder to calculate whether its proposed diversion rates are practically achievable or not.

90% for paper ‘just isn’t going to happen’

And if the ministry is expecting paper to ride to the rescue, forget it. Paper material is the single largest component of the Blue Box with 67% of it currently being recovered for recycling. The ministry’s proposed paper diversion target for 2026 and beyond, however, is 90%.

“Ninety per cent just isn’t going to happen,” says Lantz. There will be even fewer newspapers in future, more online and digital transactions (therefore less paper use), and very little opportunity for significant increases in paper recovery (corrugated box diversion is already at 98%, for example). This means the paper group as a whole will likely come in with a 69% to 70% diversion rate, he says. Far short of the ministry’s wished for 90%.

“A 90% target is unreachable. This would effectively require 95% of the population capturing and putting out for recycling 97% of their paper and making sure it is not contaminated at all. And then the recycling facility would have to capture 98% of all that paper (including paper that’s shredded) and send it on to the end-market. Add in the fact that some Ontarians use paper with kindling to start their fireplaces and woodstoves in winter and burn paper, and it’s just not reasonable to expect a 90% diversion rate.”

Other material groups won’t make targets either

Rigid plastics (bottles containing water, soft drink, laundry detergent and shampoo, and mixed plastic tubs and lids, cottage cheeses and ice cream containers) currently have a diversion rate of 26 per cent. The ministry is targeting an improvement to 60% by 2030. Lantz predicts, however, that there will be little change over the next ten years, maybe an increase to 47 per cent.

As for flexible plastic packaging (currently at 8% and targeted for 40%), he says 15% may be as far as it gets, unless there is a dramatic shift to mono-materials (single-resin) flexibles, that is, stand-up plastic pouches that are much easier to capture and recycle. “Most plastics aren’t hard to sort in a material recycling facility. People just don’t put them in the recycling system like they should, and until they do, recycling rates will stay low.”

He predicts that steel and aluminum diversion through the Blue Box will improve to maybe 60% (missing the metals target). Glass packaging will also miss its target but maybe reach 75% diversion by 2030.

There are many factors that could influence these projections: pressure for higher recycled content levels; landfill bans or surcharges; alternative collection systems including deposit/return; and the impact of the extra tonnes the ministry wants collected from a wider range of sources.

There are also behavioural changes that could influence the results. “It often boils down to that flick of the wrist decision where the householder decides whether to put something into the garbage or into the box,’’ says Lantz. “We need to be much clearer about what goes where, and to give people more opportunities to make the right decision.”

Lantz suggests the province should set disposal targets instead, thereby reducing the burden on municipalities that have to handle the recyclables that householders place in the garbage. Environmentally, he says, it would be better if we reduced consumption at the front end. “Setting unreachable diversion targets that effectively allow unfettered consumption, and relying on recycling to overcome that consumption, is not the best approach.”

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes