A new Canadian federal government study examining the cost implications of reducing plastic packaging for fresh produce sold in Canada provides insight into how the produce sector approaches packaging decisions. While the study focuses on economic and functional considerations, reviewing its findings through an environmental lens raises questions about how sustainable packaging decisions are made in practice.

This blog provides an environmental perspective on selected aspects of the study, including the example of switching apples from plastic packaging to paper and the recommendation to further examine reusable plastic crates (RPCs).

Packaging serves important functions, including protecting products, supporting transportation and logistics, and helping to reduce food waste. However, packaging decisions cannot be viewed in isolation.

As the study itself acknowledges, today’s retail environment – shaped by larger grocery stores, multiple retailers, global supply chains, and growing demand for consumer convenience – means the same product can now be packaged, or not packaged, in multiple ways. These real-world factors increasingly influence how food is packaged and sold.

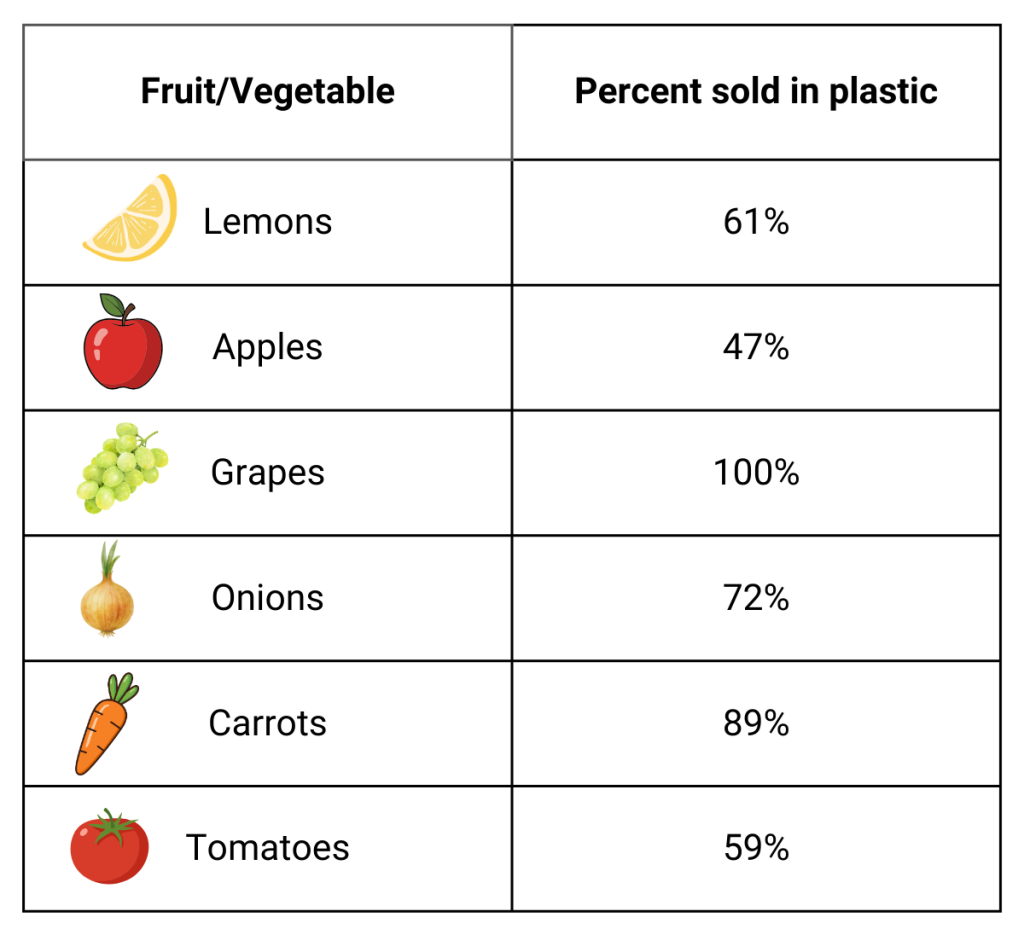

At the same time, plastic packaging remains pervasive. In 2024 alone, an estimated 400 million tonnes of plastic waste were generated, and without major changes, global plastic waste could triple, reaching around 1.2 billion tonnes by 2060. When it comes to plastic packaging for produce, the report shares the following data:

That seems like a substantial amount of plastic associated with just one segment of the food system. For additional context, a 2024 Retail Economics study found that 45% of plastic food packaging could be replaced either by transitioning to alternative packaging or by selling products loose.

PPEC’s commentary does not question the importance or function of packaging for fresh produce; rather, it questions whether all packaging currently used is required for product protection.

With that context in mind, the following sections examine aspects of the federal study to illustrate how packaging decisions are shaped by retail practices, consumer behaviour, as well as broader system-level and policy considerations.

Apples and Material Substitution

Using apples as an example, the report notes that Canadian retail store audits showed loose apples were priced 39% higher by weight than packaged apples, and further estimates that switching apples from plastic packaging to paper packaging could increase retail prices by approximately 42 per cent.

This example raises a question that extends beyond pricing alone: why are apples packaged in the first place? Apples have historically been sold loose and generally do not require primary (consumer-facing) packaging for protection. Yet the report’s cost comparison reflects a retail environment in which plastic-packaged apples are priced lower than their loose counterparts.

PPEC is not commenting on retail pricing strategies. Rather, this example illustrates how efforts to reduce plastic packaging can be complicated by existing market and consumer practices. If the objective is to reduce unnecessary packaging, it becomes important to distinguish between packaging required for product protection and packaging that exists for other reasons within retail systems.

PPEC is not looking to debate packaging decisions for every individual fruit or vegetable. However, we are observing an increase in pre-packaged produce. These formats appear to be driven by downstream retail practices and consumer expectations. This is not a critique of business decisions, but a reminder that packaging choices can sometimes run counter to environmental objectives.

This example reinforces the need to look beyond material substitution and consider how packaging decisions are shaped by modern retail practices and consumer behaviour.

Reusable Plastic Crates (RPCs)

Corrugated packaging has played a role in the fresh produce sector for decades. In Canada, corrugated cartons are part of a well-established recycling system, with strong end markets, including PPEC members that purchase and recycle used corrugated packaging from grocery and retail sectors.

Against this backdrop, it may seem counterintuitive that a study examining the implications of measures to address plastic packaging waste also explores replacing corrugated cartons with reusable plastic crates (RPCs). While RPCs may be presented as a circular option, they remain plastic, a material the federal government is actively seeking to reduce, whereas corrugated packaging is already part of a mature circular system. Although referred to as “single-use” in the study, corrugated containers are typically recycled and reused multiple times.

In practice, many packaging materials are used once by consumers, but they differ significantly in how effectively they are recovered and recycled. Paper packaging is a clear example of a material with established recycling systems and strong end markets that enable repeated reuse of fibres.

This raises a broader question about how plastic packaging reduction is being defined: does replacing recyclable fibre packaging with RPCs meaningfully advance efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and plastics?

Further, while some RPC providers cite environmental benefits such as high reuse rates and recyclability, these outcomes are dependent on system design and performance. Claims of recyclability often reflect technical recyclability within controlled or closed-loop systems, rather than real-world recycling systems across jurisdictions.

While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, the federal study serves as a reminder that produce packaging decisions are complex and cannot be viewed in isolation. As governments consider policy and regulatory changes, and businesses make packaging decisions, asking questions that reflect real world considerations – including whether packaging is necessary for product protection or has developed in response to changes in how food is purchased and consumed – is critical to advancing meaningful and scalable plastic reduction efforts.